Museum History

The Beginnings of the Collection

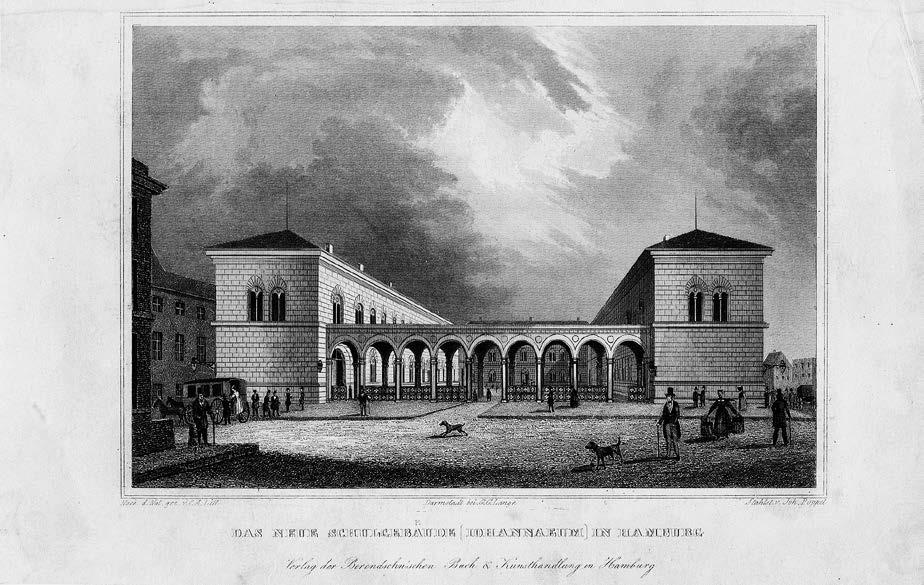

The history of the museum began with the modest ethnographic collection of the Hamburg city library. Since the 1840s its objects were housed in the Johanneum, today the oldest grammar school in the city. However, there is no evidence that the objects, collected through donations from citizens, were ever exhibited there.

In 1867, the Natural Science Association took over the management of the collection. Under Adolph Oberdörffer and Ferdinand Worlée, the 645 ethnographic objects for the first time were recorded in an index, cleaned and made accessible to the public in the rooms of the Natural History Museum. At the same time, Oberdörffer and Worlée initiated that the collection would be categorized according to the regions of Asia, America, Africa, Australia and Europe. In 1871, the collection was given its first name – Culturgeschichtliches Museum (Museum of Cultural History). Having thus become considerably more visible, there was an increasing desire in the city for a museum building of its own. This request was gladly granted in Hamburg, as there was a growing interest in research of so-called “non-European” cultural forms.

Since the mid-19th century, museums of this new type – ethnological museums – have been founded in numerous European cultural centers. Hence, the object collection from various geographical regions promised not only academic knowledge but also increasing international reputation. Closely linked with the establishing academic discipline of anthropology, museums not only made a distinction between “European” and “non-European” cultures, but also attempted to categorize people and cultures according to similarities and differences. From this grew a hierarchical model, which assumed the evolution of so-called “primitive peoples” into “civilized peoples”. The same hierarchization was employed on the related objects and the knowledge productions attributed to them.

The Limitation of the Inventory

In 1878, the Culturgeschichtliches Museum (Museum of Cultural History) moved to the new building of the vocational school at Steintorplatz. In 1879, the museum was renamed the Museum für Völkerkunde (Museum of Ethnology) in order to enhance its own collection profile compared to the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe (Museum for Art and Design), which was founded in 1874. And, following patterns of colonial classification, non-European and ethnographic objects were from then on systematically separated from an art and design inventory.

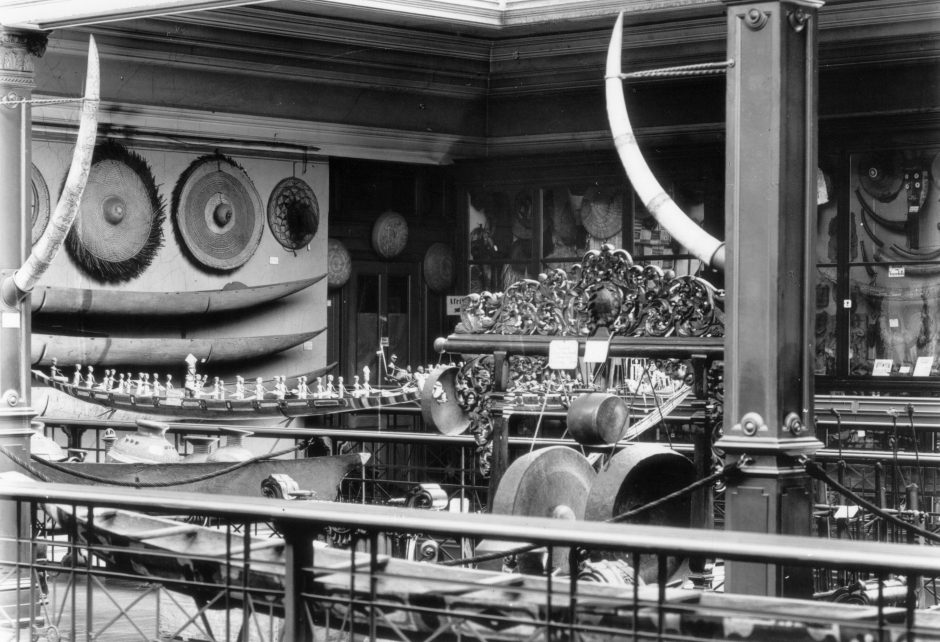

The museum enjoyed great popularity at that time. Under changing direction – until 1896 the Hamburg overseas merchant Carl W. Lüders managed the house, subsequently, the directorial assistant Karl Hagen managed it provisionally until 1904 – the number of visitors steadily increased, as did the funds for the maintenance of the collection. The collection itself multiplied every year through numerous donations. In 1879, the museum had an inventory of 1,834 objects. At the time of Lüder’s death in 1896, the ethnographic collection had already grown to 11,946 pieces. The library – today approx. 90,000 books and 200 current periodicals – comprised about 790 volumes at that time. The prevailing lack of space was only temporarily remedied by a further relocation to the gallery level of the Naturhistorisches Museum (Museum of Natural History) at Schweinemarkt in the autumn of 1890.

Hamburg’s extensive trade links and their interconnectedness in European colonialism significantly contributed to the expansion of the collection. Furthermore, there was the assumption that certain cultures were threatened by Western modernization processes. The collection of respective objects was supposed to “preserve” the knowledge about these cultures – a reasoning that was frequently reiterated. Another important objective of the emerging ethnographic museums was to generate knowledge about the cultural history of mankind, which was to be made accessible by studying and comparing the material artifacts. Besides, this was also a matter of defining one’s own (European) identity as distinct from “non-European” cultures. By depicting and hierarchizing “peoples” in exhibitions in a static and completed way the museums took part in underpinning the existing images of the power and superiority of Europe and modern science. This in turn supported the legitimization of colonial politics – going hand in hand with the then popular display of people and objects in colonial and world exhibitions. The best-known example in Hamburg was the so-called “Völkerschauen” (ethnological expositions) by Carl Hagenbeck.

Under Karl Hagen’s provisional management (1896 to 1904), the collection continued to grow to around 20,000 objects. During these years, around 50 works of art from the Kingdom of Benin were acquired, which came on sale as a result of a British colonial war in 1897. The circumstances under which these objects found their way into the museum have not yet been fully clarified and are one of the many research tasks to which the Museum am Rothenbaum and other institutions are dedicated.

Under One’s Own Roof

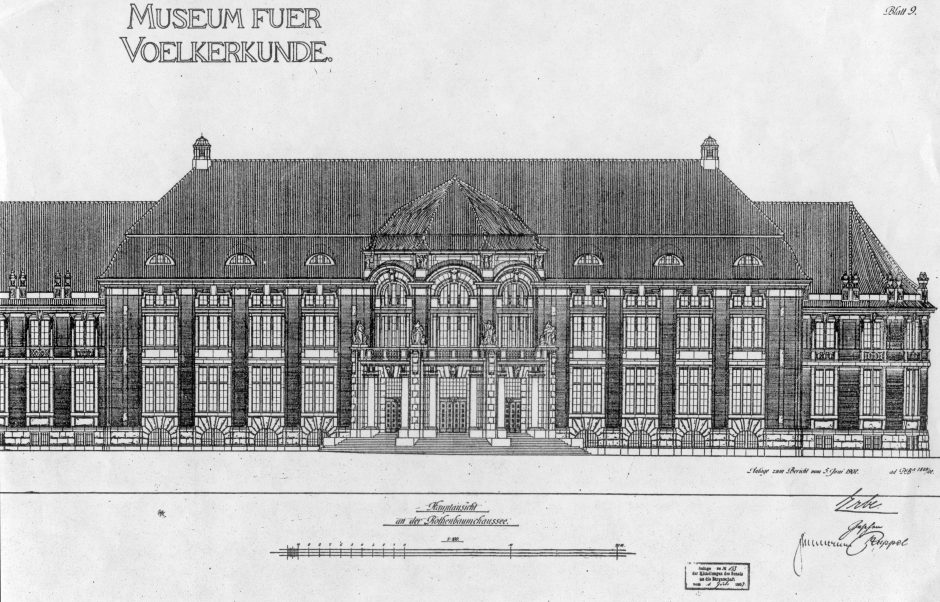

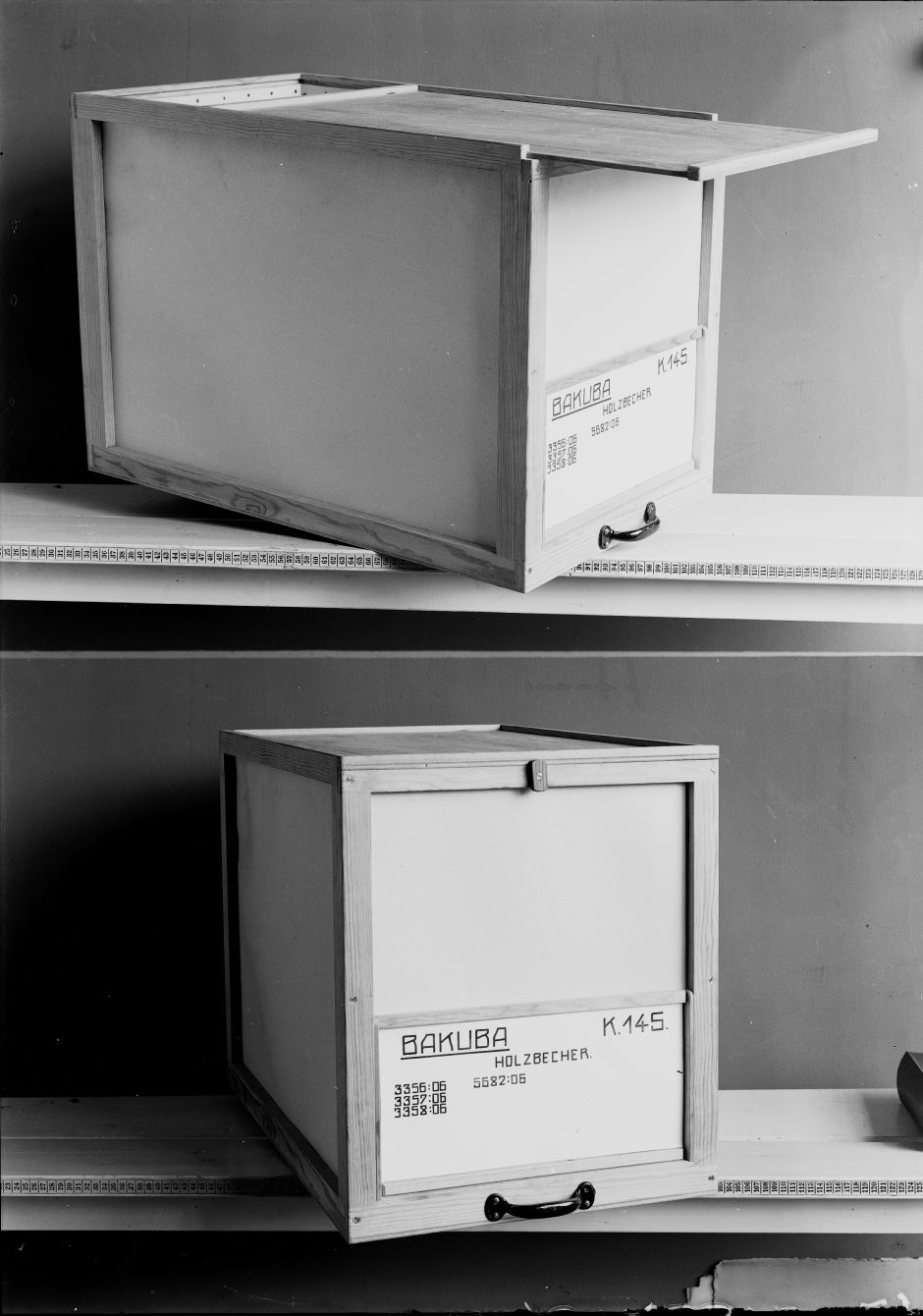

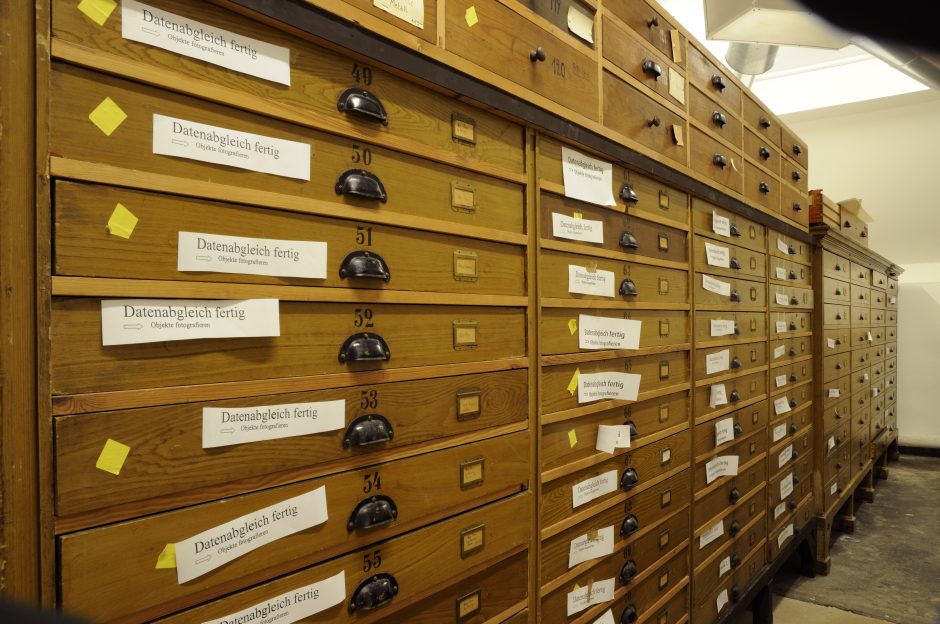

Due to the rapid growth of the collection, Karl Hagen had already begun to conduct intensive negotiations with the Hamburg Senate (government) and the Bürgerschaft (parliament) about a new building on Rothenbaumchaussee as well as the appointment of a director. In particular, prominent donors expected their objects not only to serve study purposes but also to be accessible in exhibitions. As a result, Georg Thilenius was appointed the museum’s first full-time director in 1904. With an eye to other ethnographic collections in Germany, the Senate also expanded the staff and increased the acquisition funds. One major aim was to improve work processes in the collection management. Among the important changes during this period were the division of tasks among researchers by region, the creation of first scientific positions in the field of conservation, the increase in the number of technical assistants (especially draftswomen), the establishment of a photographic workshop together with the employment of a photographer, and the establishment of a photo archive by separating the photographic objects from the library holdings. As a result of the accelerated industrialization of photography, large collections of pictures had already been gathered in the museum in the 1890s. They formed the basis of today’s photographic collection, which comprises almost 450,000 numbers.

The decision for a new building was finally made in 1908. Four years later it was completed by Albert Erbe in late Jugendstil, today it is a listed building. Originally it was only intended as the first part of a future building project. However, the second half of the building, an extension up to Feldbrunnenstraße, was never to be realized due to the following world wars. Also the new rooms were only occupied step by step. The permanent exhibition planned for 1914 in the showrooms could only be partly opened in 1921 due to the First World War; the workspaces for the employees were not even completed until 1929. However, Georg Thilenius used the inauguration of the building in 1912 for a major special exhibition: On the occasion of the general meeting of the Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft (German Colonial Society), the museum presented a selection of objects collected during the Hamburg South Sea Expedition (1908/10), the second German Inner Africa Research Expedition led by Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg (1910/11) and the East Africa Expedition of the Hamburg Geographical Society led by Erich Obst (1910/12) – in other words, collections of objects which the museum, the city and numerous Hamburg merchants had procured and which had just been brought to Europe.

Under the management of Thilenius, the collections, which until then had been collected rather unsystematically, were newly coordinated in terms of quality and quantity. Numerous ethnologists and travelers were commissioned to acquire possibly cohesive collections of objects, so that by 1915 the holdings had grown to around 100,000 objects. The museum pursued an acquisition policy that aimed to increase the distinctiveness of the museum through unique specimens. This was intended to strengthen Hamburg’s position in comparison to similar museums in Germany and Europe. At the same time, Thilenius focused on the establishment of scientific collections, as demanded not least by the Hamburg Colonial Institute (Kolonialinstitut) for its own purposes. Thilenius was substantially involved in its founding in 1908, and both institutions were closely linked for a long time.

From today’s perspective, the collecting mania of the colonial era still raises many questions. One of them concerns the impact of collecting practices on the societies of origin, prevailing not only in Hamburg, but in all comparable institutions of that time. Their problematic nature is reflected in today’s intensive debates on the possibilities of restituting objects and in the steady increase in projects researching circumstances of acquisition.

When he took office, Thilenius was already planning to establish an anthropological collection. The collection grew rapidly through purchases and donations of human remains, hair samples, casts of faces and body parts of living persons from various regions, as well as through targeted collection activities during expeditions and finds from Hamburg cemetery sites and construction sites. From 1907 to 1924 the Anthropological Department was under the direction of the later influential “race expert” Otto Reche.

Wars, Crises and Losses

The years of the First World War, the world economic crisis and the period of National Socialism were marked by many difficulties and ideologically determined changes. These ranged from the reduction of personnel and budgets to interventions in the exhibition collections. In 1934, for example, all objects belonging to the Gesellschaft für jüdische Volkskunde were removed from display and Jewish employees lost their jobs.

In 1928 the “Rassenkundliche Schausammlung” was opened under the direction of the later “racial biologist” Walter Scheidt. From 1924 to 1933 he headed the Anthropological Department and in 1933 he took over the management of the “Rassenbiologisches Institut” (Institute of Racial Biology) of the University of Hamburg, which was housed in the museum’s premises until 1944. Shortly after Thilenius retired in 1935 and the Americanist Franz Termer took over the management of the museum, the house was renamed the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology and Prehistory to emphasise its local patriotic character.

In 1953 the human remains in the collection were given to the Institute of Anatomy at the University of Göttingen and the anthropological collection was dissolved. The research project “Sensitive Provenance – Human Remains from Colonial Contexts” is currently being carried out at the University of Göttingen, which is working on the provenance of the collection. The history of the department in the museum requires a comprehensive reappraisal and will be the subject of the new permanent exhibition currently under development. Among other things, the position of the museum during the National Socialist era is to be examined more closely against the background of the revival of colonial thought at the time.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Termer and the museum staff were particularly concerned with protecting and safely storing the collections. When the air-raid shelter in the museum intended for the staff was declared a public air-raid shelter right at the beginning of the war, a large part of the Eurasia magazine had to be cleared. All the collections stored in the attic were also moved to parts of the exhibition halls because of the risk of fire. The building itself was damaged by air raids in 1940, 1942-43 and 1945. Staff who had lost their flats were accommodated in the museum. The collections were moved to supposedly safe places, but the museum nevertheless suffered heavy losses during the war. In Lautenthal in the Harz Mountains near Goslar, it lost a large part of its South Sea holdings as well as important parts of the collections of Leo Frobenius and the North and Central American departments during the last days of the war.

Post-war period and modernization

After the end of the war, the museum struggled for a long time to absorb the losses suffered in terms of staff, budget and collection items. Due to its close connection to National Socialist racial ideologies, ethnology played only a minor role in the public mind. As a result, the museum received the lowest subsidies of any of Hamburg’s museums. Likewise, the realization of the second part of the building, which had been planned for years, once again failed in 1958. Nevertheless, the 1960s were marked by fundamental renovation and modernization work, for which Franz Termer (until 1962), Erhard Schlesier (until 1967) and Hans Fischer (until 1971) were responsible. These included the repair of war damage and the organization of the collection’s stack-rooms as well as the re-planning of the showrooms. The end of Fischer’s term in office also terminated the tradition of representing both the museum and the university subject of ethnology in personal union.

At the beginning of the term of Africanist Jürgen Zwernemann as director (1971 to 1991), all of the Hamburg collections of pre- and early history were combined at the Helms Museum, today’s Hamburg Archaeological Museum (Archäologischen Museum Hamburg). With the dissolution of the Department of Prehistory, which had been part of the museum for more than 80 years, parts of the library also went to the relevant university department. A Senate decision changed the name of the museum to Hamburgisches Museum für Völkerkunde (The Hamburg Museum of Ethnology). In order to keep the museum attractive, Zwernemann once again was in favor of changes. In the 1970s and 1980s, he modernized the permanent exhibition and established a department for museum education. Zwernemann promoted field research by museum curators, in the course of which collections were acquired for the museum. Furthermore, the exhibition program focused on “non-European” art, and the museum presented exhibitions of modern art from various regions. One particular focus of research and collection was the handicraft traditions that led to the idea of a “market of peoples”. 1972 saw the foundation of a sponsoring society (Förderkreis) and the management of the collection was separated from restoration. In 1988, the museum finally managed to initiate the restitution of collection items that had been kept in Dresden during the Second World War.

Debates on the Future

At the end of the 1980s, a general debate arose in Germany about ethnological museums as a museum type. The cultural policy in Hamburg suggested changing the program as a whole and concentrating more on “new developments in countries of other continents, especially in third world countries” (the cultural concept of ‘89). There was even talk of a “Museum of the Third World” that was to strengthen Hamburg’s intercultural infrastructure. Against this background, the museum under the direction of Wulf Köpke (1992 to 2016) opted for the mission statement “One Roof For All Cultures”. Its aim was to focus on issues of European identity and integration, migration, the cultural and political upheavals in Africa, Latin America and Asia, and various forms of religion.

In 1999, the museum was converted into a foundation under public law and renamed the Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg (Museum of Ethnology, Hamburg). One of the numerous construction projects in the following years was to establish a museum restaurant in the building. Regarding research, for the first time projects were devoted exclusively to the photographic collections of the America, Middle East and Oceania region departments. At the same time, the planning of a general inventory began, in the course of which the database-supported recording of the museum collection was introduced in 2009.

The Repositioning of the Museum

Since Barbara Plankensteiner’s appointment to the post of director in April 2017, a phase of restructuring began for the museum, which will also result in alterations and the renovation of the building as well as in a lasting solution for the depot of the collection and archive holdings. In terms of content, the museum is working on a new concept for the permanent exhibition along thematic lines and in historical contexts, as well as on changed objectives for temporary exhibitions that are already visible, and also on the development of event and communication formats that meet the diverse interests of urban society.

The great potential of the museum and its impressive collection, which is closely linked to Hamburg’s historical identity, is to be exploited in a new way. At the same time, the museum intends to establish itself as a reflexive forum that critically examines traces of the colonial heritage, traditional patterns of thinking, and issues of the postmigrant globalized urban society. Today, the focus is no longer on depicting peoples. Rather, the focus is on the cultural anchoring of people, on the appreciation of coherences, similarities and differences, and on the diversity of cultural and artistic achievements of the world.

The repositioning is an ongoing and extensive process that will accompany the museum over the next few years. An important step was taken by renaming it Museum am Rothenbaum / Kulturen und Künste der Welt*, short: MARKK, which was effected in 2018. Each new exhibition and many of the events are small facets in the big picture.

Follow our developments in the museum and on the website, take part and accompany us on our way!

* World Cultures and Arts